Sustainable Business

The Origins and Business Basics of Sustainability and ESG

The concept of sustainability originates from “sustainable development“, first defined in the 1987 UN publication Our Common Future. After 900 days of global meetings, the report emphasized the need to balance economic growth, environmental protection, and social equity.

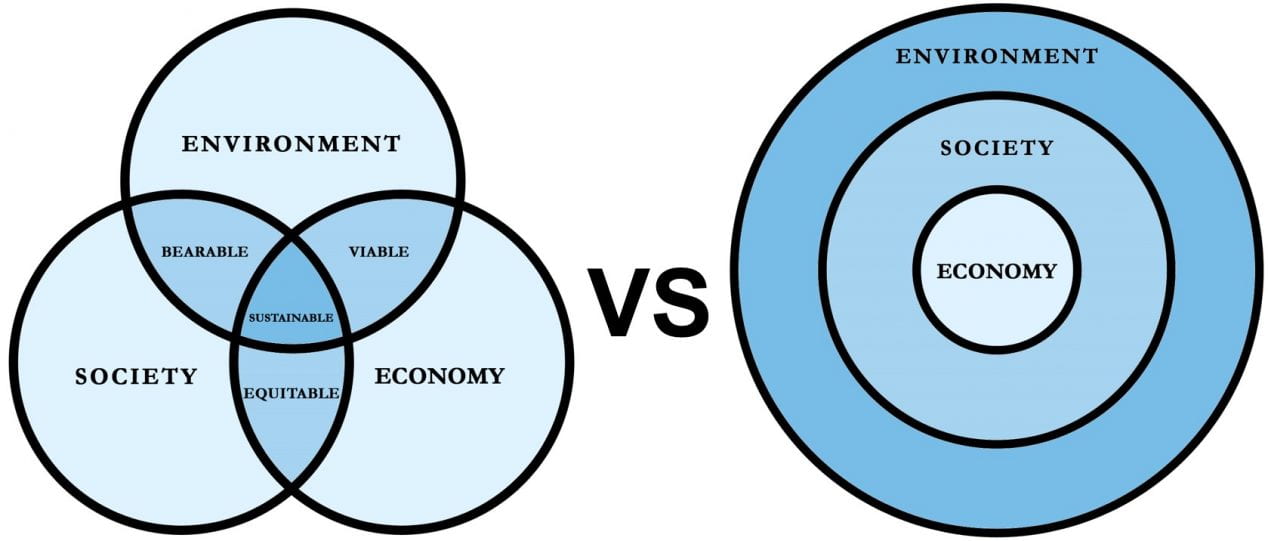

This balance is often summed up as people, planet, and profit. In business, it is known as the triple bottom line, a concept introduced by sustainability expert John Elkington in the 1990s. The diagram to the right illustrates how these three areas overlap.

While some mistakenly believe sustainability is only about the environment, it also includes human rights, equity, and economic opportunity. As the Our Common Future report notes:

“Poverty is a major cause and effect of global environmental problems.”

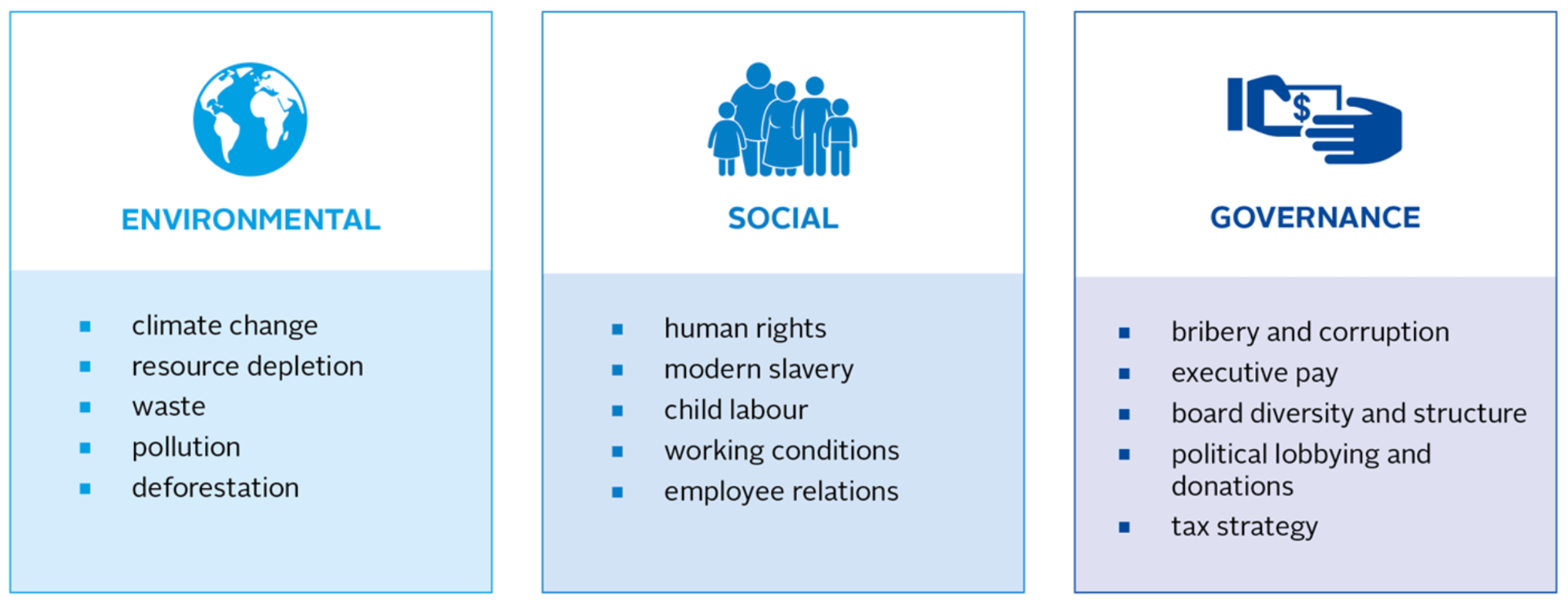

In 2005, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) was coined by the United Nations Environment Programme Initiative, as outlined in the Freshfields Report and the Who Cares Wins Brief from the UN Global Compact.

Today, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a global blueprint for addressing climate change, reducing inequality, and building inclusive prosperity.

To explore a more in-depth development of ESG over time, see this timeline and history of ESG investing and this overview of ESG’s evolution and impact.

The Business Case for Sustainability & ESG

A common but outdated misconception among some executives is that sustainability is too costly and that social and environmental issues are solely the responsibility of governments and the non-profit sector.

However, as issues like climate change and human rights violations increasingly affect businesses, ignoring sustainability has become a significant risk. Research shows that embedding sustainability into a company’s core business strategy benefits society and delivers positive financial returns.

The graphic on the left illustrates eight ways sustainability can drive financial success in both the short and long term.

According to the Harvard Business Review’s The Comprehensive Business Case for Sustainability, sustainable practices enhance competitive advantage, risk management, innovation, financial performance, customer loyalty, and employee engagement.

To see companies leading the way in making sustainability a core business strategy, explore Barron’s List of the Top 100 Sustainability Companies or the Sustainability Magazine’s Top 250 Sustainability Leaders

Defining the Three Pillars of Sustainability

People: The Social Bottom Line

Companies that follow the triple bottom line framework consider both the intended and unintended impacts of their operations on people.

Internal practices may include:

- Comprehensive healthcare

- Paid maternity and paternity leave

- Fair working hours

- Advancing diversity and inclusion

External efforts may include:

- Protecting labor rights across the supply chain

- Prioritizing supplier diversity

- Evaluating the social impact of investments

- Supporting local communities by addressing inequalities in access to:

-

- Education

- Healthcare

- Clean drinking water

-

Planet: The Environment Bottom Line

Triple bottom line companies aim to reduce or eliminate their ecological footprint by evaluating the full life cycle of their operations and products and measuring environmental costs at both global and local levels.

Global impacts may include:

- Climate change

- Ocean acidification

- Loss of biodiversity

- Pandemics

Local impacts may include:

- Water use and pollution

- Soil degradation

- Localized air pollution

- Damage to natural areas

Profit: The Economic Bottom Line

Profitability and competitiveness are essential for companies to survive and create lasting positive change.

From a triple bottom line perspective, profit should:

- Empower and sustain communities, not just CEOs and shareholders

- Be driven by progress across the social and environmental bottom lines

When done well, this approach could look like reducing water use in manufacturing, which lowers environmental impact and operational costs.

Other responsible financial strategies include:

- Offering reasonable and transparent executive compensation

- Adopting ethical lobbying and investment practices

- Reinvesting profits to foster innovation and social good

Case Study Examples: The Many Faces of Sustainable Business

Circular Economy

Fairphone’s modular smartphone design keeps devices in use longer by making parts easily replaceable and repairable. This reduces electronic waste and promotes sustainable use of materials

Social Innovation

Warby Parker’s “Buy a Pair, Give a Pair” program pairs affordable style with social impact by providing quality eyewear to people in need worldwide.

What Drives Sustainability & ESG?

While many factors drive sustainability, four core forces tend to shape and amplify the rest: population growth, intensive resource consumption, climate change, and inequality. Each year, the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report highlights these and other emerging social and environmental trends that are reshaping business and society.

Sustainable Development Goals

One of the most widely recognized responses to today’s social, economic, and environmental challenges is the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These 17 interconnected goals aim to address global issues such as poverty, education, and climate change by 2030. The SDGs are commonly referenced in sustainability and ESG conversations, particularly among organizations committed to impact-driven work. Tools like the SDG Compass support efforts to integrate the goals into strategy, culture, and operations.

And Finally…Sustainable Business/ESG is Not Without It’s Critics

Sustainable business, social responsibility, ESG, and social entrepreneurship are exciting concepts about “doing well while doing good” but are not without their critics. The most thoughtful contrarians are worth listening to as their warnings can keep sustainability from running afoul of its higher purposes (and legal requirements). The skillful and informed student and professional needs to understand these basic critiques.

Here we will provide a brief overview of the two main lines of criticism:

Critique #1: Sustainability is about sustaining the business– attracting employees and customers, accessing new markets, lowering costs and avoiding regulations–and not about making any measurable changes to how it impacts people and the planet.

“What we call ‘eco-business’–taking over the idea of sustainability and turning it into a tool of business control and growth that projects an image of corporate social responsibility–is proving to be a powerful strategy for corporations in a rapidly globalizing economy marked by financial turmoil and a need for continual strategic repositioning…True or ‘deep’ sustainability requires restoring and protecting ecosystems and communities, and not, as every big brand is doing, first and foremost trying to use sustainability to enhance the efficiency of production and the quality of products to speed along growth.” (Peter Dauvergne and Jane Lister, Eco-Business: A Big Brand Takeover of Sustainability, 2013)

Critique #2: Sustainability is a distraction and drain on the profit-making function and legal responsibility of the enterprise

“The business [people] believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned ‘merely’ with profit but also with promoting desirable ‘social’ ends; that business has a ‘social conscience’ and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers.”

“In fact they are—or would be if they or any one else took them seriously— preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.” (Milton Freedman, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits”, NY Times, 1970)